In the decades prior to the 1950s, both black music and white not only co-existed, but inspired each other. It’s fairly common knowledge that many country artists incorporated the black blues style into THEIR style (i.e. Jimmie Rodgers and Hank Williams) but not many people are aware that black artists were, in turn, inspired by white artists: bluesman Robert Johnson is said to have performed “Tumbling Tumbleweeds” and material by the father of country music, Jimmie Rodgers, in live performance.

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]ne of R&B shouter Roy Brown’s idols was Bing Crosby. Wynonie Harris – another R&B shouter – covered country singer Hank Penny’s “Bloodshot Eyes”. Jazz giant Charlie Parker played Roy Acuff records on the jukebox, much to the amusement of his bandmates.

Part One: Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup

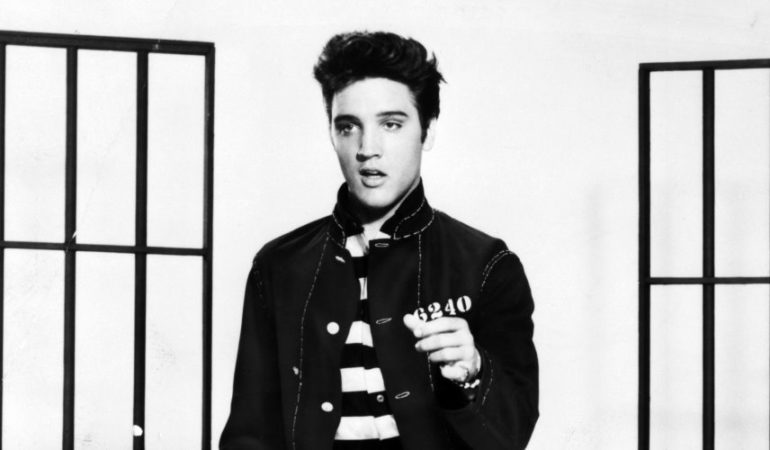

Both sides came together quite powerfully in 1954 with the release of Elvis’ debut single: one side featured “That’s All Right,” a tune written and recorded by bluesman Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup on September 6, 1946; the other “Blue Moon of Kentucky,” a country piece by Bill Monroe & His Blue Grass boys.

[pullquote-left]My view is that rock’n’roll did not begin with Sun Records, Elvis, Bill Haley or anyone else to that made their mark in the 1950s.[/pullquote-left] What happened was that black music was being discovered by an ever-growing number of black and, more importantly, white, teenagers, and those teenagers had more money than previous generations. What did they spend their money on? Records, for one, and by doing so they popularized what already existed, causing rock’n’roll – which had been around for decades, known largely throughout the South and in black communities – to unleash itself on an unsuspecting nation.

But a new generation of rockers had been born; the ones from the pre-1950s period were largely – and sadly – forgotten. One suggestion – and there’s been several – has been that record companies wasted no time promoting then-new rockers such as Elvis, Chuck Berry and Little Richard and therefore couldn’t be bothered reissuing their older catalogs (in addition to Chuck Berry, Chess also had Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf; in addition to Little Richard, Speciality also had Joe and Jimmy Liggins, and so forth.)

But a new generation of rockers had been born; the ones from the pre-1950s period were largely – and sadly – forgotten. One suggestion – and there’s been several – has been that record companies wasted no time promoting then-new rockers such as Elvis, Chuck Berry and Little Richard and therefore couldn’t be bothered reissuing their older catalogs (in addition to Chuck Berry, Chess also had Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf; in addition to Little Richard, Speciality also had Joe and Jimmy Liggins, and so forth.)

The music has been evolving since the dawn of the recording industry in the 1890s. The first black music to be recorded were spirituals. It hardly matters what one calls it, be it folk music, variations on the blues, or rock ‘n’ roll. What matters most of all is that people realize that music, i.e. pop/rock, is all connected and that it all comes from the same source. In my personal opinion, that source is the African field holler. It is my hope that the connection between musical styles is evident, if even slightly, as we examine the original versions of songs covered by Elvis Presley.

Personnel on the original “That’s All Right” is: Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup, guitar and vocal; Ransom Knowling, bass and Judge Riley, drums. The sound, though from the R&B/blues mold, is almost rockabilly in nature.

I’ll wrap this essay up with a quote from Elvis the Pelvis himself from a 1956 interview:

The Colored folks been singing it and playing it just like I’m doin’ now, man, for more years than I know… they played it like that in the shanties and juke joints, and nobody paid it no mind till I goosed it up. I got it from them. Down in Tupelo, Mississippi, I used to hear old Arthur Crudup bang his box the way I do now, and I said if I ever got to the place I could feel what old Arthur felt, I’d be a music man like nobody ever saw.

Part Two

Yesterday we featured the original version of the song that filled one side of Elvis’ debut single, “That’s All Right”. Today we feature the original version of the flip, “Blue Moon of Kentucky” by Bill Monroe & His Bluegrass boys, recorded on September 16, 1946 for Columbia Records – only 10 days after Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup cut “That’s All Right” for Bluebird.

The song features Monroe on lead vocals and mandolin, Lester Flatt on guitar, Earl Scruggs on banjo, Chubby Wise on fiddle and Howard Watts on string bass.

Elvis recorded both “That’s All Right” and “Blue Moon of Kentucky” between July 5th and 6th, 1954; possibly even on the same day. It was released that same month as Sun 209. Sam Phillips (owner of Sun) took both recordings to Memphis DJ Dewey Phillips (no relation to Sam) and played them for him. Convinced it was a hit record, Dewey wanted to play it on his show immediately, so Sam cut acetates of the recordings for Dewey to play and he wound up playing both sides many times over, causing what has been said to be a total of 47 calls to the station along with 14 telegrams wanting to know “what was that?!?!”

Elvis recorded both “That’s All Right” and “Blue Moon of Kentucky” between July 5th and 6th, 1954; possibly even on the same day. It was released that same month as Sun 209. Sam Phillips (owner of Sun) took both recordings to Memphis DJ Dewey Phillips (no relation to Sam) and played them for him. Convinced it was a hit record, Dewey wanted to play it on his show immediately, so Sam cut acetates of the recordings for Dewey to play and he wound up playing both sides many times over, causing what has been said to be a total of 47 calls to the station along with 14 telegrams wanting to know “what was that?!?!”

On Thursday July 8th, Dewey had interviewed Elvis in the studio. Since everyone thought Elvis was black, one of the things that Dewey asked him was where he went to high school. Elvis said “Humes” – proving that Elvis was, in fact, white since Humes was an all-white school.

The record wound up being a local smash. In fact, the success of Elvis’ debut caused Bill Monroe to recut “Blue Moon of Kentucky” in the same style that Elvis cut his – rockabilly! (I should say here that rockabilly in the ’50s was really nothing new, either: in the ’40s it was called hillbilly boogie, a style performed by Hank Williams, The Delmore Brothers, Hardrock Gunter and Roy Hall, to name a few. Look for these artists in future editions of ‘Roots’.)

http://youtu.be/G5kNVizmNL4

Part Three: Good Rockin’ Tonight

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n 1946, R&B shouter Roy Brown wrote a song called “Good Rockin’ Tonight”. In 1947 he approached his idol, fellow R&B shouter Wynonie Harris, with the tune and offered it to him. He declined the offer. Brown then played the song for R&B pianist Cecil Gant, who was playing down the street. Gant loved the song so much that he called the head of DeLuxe Records Jules Braun at 4am and had Roy sing it to him over the phone. Braun signed Roy, who would record the original version of “Good Rockin’ Tonight” in New Orleans for DeLuxe in July 1947. It was released as DeLuxe 1093 and hit #13 on the race charts (it wasn’t called R&B until 1949).

The success of Brown’s single finally caused Harris to record his version of the song, which he did in Cincinnati on December 28, 1947. It was released as King 4210 and by June of ’48 would reach #1 on the race charts, ushering in a tougher brand of R&B and inspiring countless songs with the word “rocking” in its title in the process.

[pullquote-left]It was most likely the Wynonie Harris version which inspired Elvis to record “Good Rockin’ Tonight,”[/pullquote-left] which he cut in September of ’54 and would become his second single for Sun, released sometime during that month with “I Don’t Care If The Sun Don’t Shine” on the flip as Sun 210. After all, it was while watching Wynonie Harris perform in Memphis in the early 1950s that Elvis learned to curl his lip and swivel his hips.

Personnel on the Roy Brown version of “Good Rockin’ Tonight” includes Tony Moret on trumpet, Clement Tervalone on trombone, O’Neil Jerome on alto sax and Robert Ogden on drums (other personnel unknown). Personnel on the Wynonie Harris version include jazz veteran Hot Lips Page on trumpet, Joe Britton on trombone, Vincent Bair-Bey on alto sax, Tom Archia and Hal Singer on tenor saxes, Joe Knight on piano, Carl “Flat Top” Wilson on bass and Clarence “Bobby” Donaldson on drums.

Part Four: Hound Dog

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]hile it is fairly common knowledge that the original version of “Hound Dog” was written by Lieber and Stoller and was first released by blues belter Big Mama Thornton in 1953, and that Elvis’ version was released in 1956 as the B-side to his monster single “Don’t Be Cruel,” not many people know of a version that was sandwiched between the Thornton version and the Presley version.

Freddie Bell and the Bellboys consisted of vocalist Freddie Bell, saxophonist Jack Kane, bassist Frankie Brent, pianist Russ Conti, drummer Chick Keeney and trumpeter Jerry Mango. They brought rock’n’roll to the gambling clubs and casinos of Las Vegas and Reno. Their shows were energetic and professional. They appeared in the films Rock Around the Clock and Rumble On the Docks and toured Britain, France, Manila, Australia, Sinagpore and Hong Kong. All of which are reasons why Freddie Bell and the Bellboys thrived without having a hit record here in the States.

Their first release was “Hound Dog,” cut in early 1955 and released on the small Teen label as Teen 101 but in April 1956 – over a year later – Elvis was booked into the New Frontier Hotel in Las Vegas. Elvis bombed but it offered him a chance to catch Freddie Bell and the Bellboys’ stage act. He was impressed and asked Bell about “Hound Dog” to which Bell told Elvis to go ahead and record it.

Their first release was “Hound Dog,” cut in early 1955 and released on the small Teen label as Teen 101 but in April 1956 – over a year later – Elvis was booked into the New Frontier Hotel in Las Vegas. Elvis bombed but it offered him a chance to catch Freddie Bell and the Bellboys’ stage act. He was impressed and asked Bell about “Hound Dog” to which Bell told Elvis to go ahead and record it.

Elvis performed “Hound Dog” on the Milton Berle Show on June 5, 1956, doing a bump-and-grind version which caused alot of controversy, which is interesting since Bell cleaned up the lyrics when covering the Thornton original, much like Bill Haley cleaned up the Big Joe Turner hit “Shake, Rattle & Roll”. Anyway, Elvis cut his version of “Hound Dog” a little over a month later – on July 2 – the day after singing the song to a basset hound on The Steve Allen Show to make up for his “dirty” appearance on the Berle show.

Until this time, all covers of “Hound Dog” copied the arrangement of the Big Mama Thornton version but when Elvis cut the song it became the only arrangement, which spurred versions by Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins, The Everly Brothers and Conway Twitty – all of which owe a debt to Freddie Bell.

According to the liner notes to Rockin’ Is Our Business, the Freddie Bell and the Bellboys CD released by Bear Family in 1996,

“Bell could see the future of his arrangement and re-recorded “Hound Dog” in May 1956, some two months previous to Presley, but Mercury sat on it and it only appeared later hidden away on Bell’s album Rock & Roll… All Flavors”. Unfortunately, Mercury wasn’t on the same page and Bell couldn’t hitch a ride on the Presley hit.”

Part Five: Tomorrow Night

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]dmittedly, I have no idea who did the original version of “Tomorrow Night”. Horace Heidt had a minor hit with it in 1939 and Lonnie Johnson cut it on December 10, 1947 for King Records. It is the Lonnie Johnson version that is the focus of this mailing.

[pullquote-left]At the time he recorded Tomorrow Night, Alonzo Lonnie Johnson was 58 years old[/pullquote-left]At the time he recorded “Tomorrow Night,” Alonzo Lonnie Johnson was 58 years old, already a recording star since 1925 (he chopped off eleven years of his life when filling out King’s artist information sheet, stating he was born in 1900, though, in all fairness, some sources place his birth year in 1899.)

Lonnie Johnson worked with Bessie Smith, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington and Buddy Guy, recorded some classic guitar duets with early jazz guitarist Eddie Lang in the late ’20s (Eddie Lang and violinist Joe Venuti were the blueprint for the classic French duo of guitarist Django Reinhardt and violinist Stephane Grappelli) and was admired so much by Robert Johnson that he claimed his middle initial “L” stood for Lonnie (as stated in the Lonnie Donegan segment of the British Blues series, Donegan adapted the name “Lonnie” in tribute to Lonnie Johnson.)

Elvis cut “Tomorrow Night,” possibly learned from Lonnie’s King version (no doubt he heard Lonnie’s version), in September of 1954, but no guitar solo was recorded. It wasn’t released until 1965 when it appeared on the album ‘Elvis For Everyone,’ complete with guitar overdubs by Chet Atkins. It was released in 1987 on ‘The Complete Sun Sessions’ but without the solo. The solo, however, is present on the 5-disc Elvis compilation “The Complete ’50s Masters” (1992) and the 2-disc collection of his Sun recordings, ‘Sunrise’ (1999)

Part Six: Mystery Train

[pullquote-left]One of the great songs to come out of the blues[/pullquote-left]One of the great songs to come out of the blues – let alone Sun Records – is the classic “Mystery Train,” originally recorded in September or October of 1953 by Little Junior’s Blue Flames and released in November as Sun 192 with “Love My Baby” on the flip. Of the two sides, Billboard picked “Mystery Train” to be the hit. It would become the follow-up to Parker’s “Feelin’ Good,” a # 5 R&B smash in 1953.

That November, while Junior Parker was on a Southern tour of one-nighters with Big Mama Thornton and Johnny Ace, Sam Phillips’ brother Jud was in Atlanta and learned that Southland Distributors wanted 1,000 copies of “Mystery Train” and urged Sam to press significant quantities in anticipation of a major hit. Wanting more artistic freedom (Parker and his band did not take “Feelin’ Good” seriously, hence its commercial success), Parker signed with Duke Records, where he stayed until the mid-1960s.

“Mystery Train” would be covered by Ricky Nelson, The Band, Paul Butterfield (who performed it with The Band for ‘The Last Waltz’ concert), Sleepy LaBeef, Jose Feliciano, Bon Jovi, The Stray Cats, Jeff Beck with Chrissie Hynde and Leon Russell to name just a few.

“Mystery Train” would be covered by Ricky Nelson, The Band, Paul Butterfield (who performed it with The Band for ‘The Last Waltz’ concert), Sleepy LaBeef, Jose Feliciano, Bon Jovi, The Stray Cats, Jeff Beck with Chrissie Hynde and Leon Russell to name just a few.

In the hands of Elvis, who recorded his version on July 11, 1955, it would become somewhat of a staple for rockabilly acts . Coupled with “I Forgot To Remember To Forget,” it would be Elvis’ fifth – and final – single for Sun (Sun 223, with “I Forgot To Remember To Forget” becoming Elvis’ first # 1 country hit while “Mystery Train” became a #11 country hit.) In total, Elvis would record 25 songs for the label before moving on to RCA later that year.

Interestingly, since Junior Parker’s records have a rockabilly feel, Sam Phillips would play Parker’s uptempo records for his rockabilly artists, instructing the guitarists to emulate Floyd Murphy’s guitar riffs. Because of this fact, we will feature “Love My Baby” – where guitarist Scotty Moore copped riffs for Elvis’ version of “Mystery Train” – in a future edition of ‘Roots’.

“Mystery Train” by Junior Parker’s Blue Flames. Personnel includes Herman Parker on vocals and harmonica, possibly Raymond Hill or James Wheeler on saxophone, Bill Johnson on piano, Floyd Murphy on guitar, Kenneth Banks on bass and John Bowers on drums

http://youtu.be/cjYQHlr83eg

Part Seven: When It Rains It Pours

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]hat do “When It Rains It Pours” and “Red Hot” have in common? In addition to having been recorded by Sun Artists, they were both written by Sun Records artist Billy “The Kid” Emerson.

Emerson cut “When It Rains It Pours” (the original title) on October 27, 1954 for Sun. It was released as Sun 214 with “Move Baby Move” on the flip. In May 1955, “When It Rains It Pours” entered the New Orleans chart, and is possibly the last chart entry Sam Phillips had with a black artist.

[pullquote-right]Elvis cut the song twice, changing its title to “When It Rains It Really Pours” in the process.[/pullquote-right] The first recording took place between August and October 1955 for Sun – his final recording for the label – with Scotty Moore, Bill Black and Johnny Bernero on drums (another source states it was recorded in November 1955 while yet another states it as having been recorded “probably July 1955”). At any rate, no master was ever made of this first version but take three – an outtake – was first issued in 1983 on the LP ‘Elvis – A Legendary Performer Volume 4′. Elvis’ second undertaking of the song took place in February 1957. This version was not released until 1965 when it was included on the ‘Elvis For Everyone’ album, featuring D.J. Fontana on drums and the Jordanaires on backing vocals.

As for the song “Red Hot,” with its memorable line

“My gal is red hot, your gal ain’t doodly squat,”

Emerson cut the original version in May 1955 (the same month that “When It Rains It Pours” entered the New Orleans chart). It would later be recorded by rockabilly artist Billy Lee Riley and his group The Little Green Men – also for Sun – possibly on January 30, 1957 (he would re-record the song for his own Rita label in 1959, but it would remain unissued until 1990, when Germany’s Bear Family Records issued it on the 2-disc Riley compilation ‘Classic Recordings: 1956-1960’. Later in 1957, “Red Hot” was recorded yet again by Bob Luman, who would attain his biggest hit in 1960 with “Let’s Think About Living” (his response to teen death songs so popular at the time). “Red Hot” was revived again in April 1977 by rockabilly artist Robert Gordon with Link Wray on lead guitar, whose instrumental “Rumble” is a ’50s rock’n’roll staple.

When It Rains It Pours” by Billy “The Kid” Emerson. Personnel includes Emerson on vocals/piano, Charles Smith on trumpet, Luther Taylor on alto saxophone, Benny Moore on tenor saxophone, Elvin Parr on guitar and Robert Prindell on drums.

Part Eight: One Night

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]n December 14, 1953 Smiley Lewis recorded the first version of “Blue Monday” for Imperial, a # 5 smash for label mate Fats Domino in 1957 (Domino played piano on the Smiley Lewis original.)

On May 23, 1955 Smiley Lewis recorded the original “I Hear You Knockin’,” a tune written by Pearl King and Dave Bartholomew, the latter a trumpet player who also wrote and arranged with Fats Domino in addition to co-writing and performing the original version of “My Ding-A-Ling” in 1952, a #1 hit for Chuck Berry twenty years later. Since Dave Bartholomew was also associated with Fats Domino, Fats would record his version of “I Hear You Knockin'” for Imperial in 1958. It would also become a # 4 hit for Dave Edmunds in 1971. But in 1955, Gale Storm’s version beat out Smiley’s on the pop charts, peaking at #2 (Smiley’s hit #2 on the R&B charts.)

On October 25, 1955 Smiley Lewis recorded the original version of the Elvis classic “One Night” but with the lyric “one night of sin is all I’m paying for…” It became a #11 R&B hit in 1956. When Elvis got his hands on the recording, he changed the lyric to “one night with you…”. Cleaned up, yes, but still suggestive.

[pullquote-left]Elvis recorded “One Night” with the ‘sin’ lyric but no doubt realized the lyrics were a bit too risque for white America[/pullquote-left]Elvis recorded “One Night” with the ‘sin’ lyric on January 24, 1957 at the “(Let Me Be Your) Teddy Bear” session but no doubt realized the lyrics were a bit too risque for white America. He re-recorded the track a month later, between February 24th and 27th. It was released in October of 1958 with “I Got Stung” on the flip. “One Night” peaked on the charts at # 4 and “I Got Stung” at # 8.

Pop success may have eluded Smiley Lewis, but he wasn’t just an artist who recorded the original versions of future pop hits. He recorded many irresistable R&B gems such as “Jailbird,” “Big Mamou,” “Bumpity Bump,” “Rootin’ & Tootin,” “Down Yonder We Go Ballin'” and “Oh Red” in addition to remakes of “Tomorrow Night” (covered by Elvis at Sun and Sunday’s “Elvis Origins” feature), the 1944 Cecil Gant hit “I Wonder” and “One Night of Sin”.

“One Night” by Smiley Lewis. Personnel includes Smiley Lewis on vocal, Ernest McLean on guitar, Frank Fields on bass, Earl Palmer on drums, Edward Frank on piano, Lee Allen and Clarence Hall on tenor saxophones, Joe Harris on alto saxophone and Dave Bartholomew on trumpet.

Part Nine: Witchcraft

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n addition to writing “One Night,” Dave Bartholomew also wrote this gem, “Witchcraft”. No, not for Frank Sinatra but rather for a New Orleans vocal group calling themselves The Spiders. Pearl King, Bartholomew’s wife, is given co-writing credit to the song for legal reasons.

On August 27, 1955, the group assembled at Cosimo Matassa’s little New Orleans studio – where Smiley Lewis, Fats Domino and Little Richard also recorded – and cut “Witchcraft” and three other tunes for Imperial Records. When released, “Witchcraft,” coupled with “(Is It True) A Little Bird Told Me” – a Pearl King composition – achieved crossover pop success as early as October and peaked at #5 on the R&B charts (the liner notes to The Spiders reissue issued by Bear Family states it peaked at #7. I’ll put my trust in Billboard.)

[pullquote-left]”Witchcraft” was one of Buddy Holly’s favorite records and so named his group The Crickets as a tribute to The Spiders.[/pullquote-left] At this point in time it’s common knowledge that The Beatles so named themselves in tribute to The Crickets.

In May 1963, Elvis recorded twelve songs for an album that never materialized, though several of the songs would be released as singles. “Witchcraft” was one of those songs, having been recorded on May 27th. It entered the Top 40 on November 9, 1963 where it stayed for three weeks, peaking at #32. The song was included on the album ‘Elvis’ Gold Records Volume 4′ in January 1968.

Personnel on “Witchcraft” includes Hayward “Chuck” Carbo, Leonard “Chick” Carbo, Joe Maxon, Matthew “Mac” West and Oliver Howard.

Part Ten: Love Me

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]s stated in a previous episode of this series, Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller wrote “Hound Dog” for Don Robey’s Peacock label. It was recorded in 1952 by Big Mama Thornton and went on to become the #1 R&B hit of 1953. Of all the songs written by Leiber and Stoller up to this point, it was “Hound Dog” that would make a lasting impression on rock’n’roll. However, all too common in the music business is greed, and that’s exactly what happened to Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller when Don Robey stopped payment on a check written out to the songwriting team. Determined never to be ripped off again, Leiber and Stoller formed their own record company: Spark Records.

Spark records was formed in 1954. The proprietors were Leiber, Stoller, Stoller’s dad A.L. Stoller, Lester Sill and Jack Levy. Between March 1954 and September 1955 they would release 22 singles, including “One Bad Stud” by The Honey Bears (covered by The Blasters, whose version appeared on the soundtrack to the film ‘Streets of Fire’ in 1984), six singles by The Robins – later to become The Coasters – including their classics “Riot In Cell Block #9” and “Smokey Joe’s Cafe” and two singles by Willy and Ruth, who recorded the original version of “Love Me” (Ruth was the wife of The Honey Bears’ bass vocalist.)

Elvis’ version of “Love Me” was recorded in early September 1956 and was included on the EP ‘Elvis Volume 1’ released that October and the LP ‘Elvis’ Golden Records’ in March 1958. It became a #2 pop hit in late 1956/early 1957.

“Love Me” was released as Spark 105 in 1954 and was the 2nd song written by Leiber & Stoller to be recorded by Elvis Presley. Elvis would go on to record several more Leiber & Stoller-penned tunes, including “Loving You,” “(You’re So Square) Baby I Don’t Care,” “Treat Me Nice,” “Don’t,” “Trouble” and “Jailhouse Rock” (one of my favorite Elvis tunes.)

http://youtu.be/cyxg8TYV7ZQ

Part Eleven: My Baby Left Me

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]e’re going to close our Elvis Origins series with the artist that opened it – Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup.

Crudup cut the original “My Baby Left Me” on November 8, 1950 for Bluebird Records. Personnel includes Crudup on guitar and vocals, Ransom Knowling on bass and Judge Riley on drums.

Elvis Presley cut his version of “My Baby Left Me” at his second RCA session, January 30th-31st and February 3, 1956. Through Elvis’ version of the song came versions by Creedence Clearwater Revival, included on their 1970 classic ‘Cosmo’s Factory,’ and Dave Edmunds, who included the song on his LP ‘Git It,’ released on Led Zeppelin’s Swan Song label in 1977

Views: 7